diana lam

Exploring Yelp's Elite

The role that Yelp plays in our commercial consumption is undeniable. For the past five or so years, I can only remember a handful of times that I’ve willingly visited a new restaurant without first poring over the place’s Yelp reviews.

Yelp itself has become a massive social network, full of users who create online personas for themselves and develop fan clubs based on their reviews and photos. Check out Victor “shanghai k” G. from Oakland. He’s written over 10,000 reviews and 3,500 friends on Yelp. If you assume it takes him 5 minutes to write a review, this guy has spent over 800 hours of his life (or 35 full days) writing Yelp reviews! Another notable is Mike C., who has made an internet celebrity of his kids by using them as food photog accessories.

Being a Yelp “elite” is the aspiration of many Yelp users. Getting awarded elite status means that not only has your community of peer users recognized you as a valuable member, but so have the-powers-that-be at Yelp corporate itself. Perks mostly include invitations to swanky foodie events where you get to network with other elites. The pathway to becoming an elite involves showcasing your “authenticity,” “contribution,” and “connection,” to Yelp’s mysterious “Elite Council.” If that sentence doesn’t make the process sound cloaked–it is. If you haven’t already guessed the topic of my next project, here it is: Can I predict whether or not a user is elite? Beyond this simple prediction, can I figure out the specific review qualities and other social metrics that make a user more likely to be granted elite status?

To kick things off, I’ve been working this week on some exploratory data analysis using the (very rich) Yelp Dataset Challenge data.

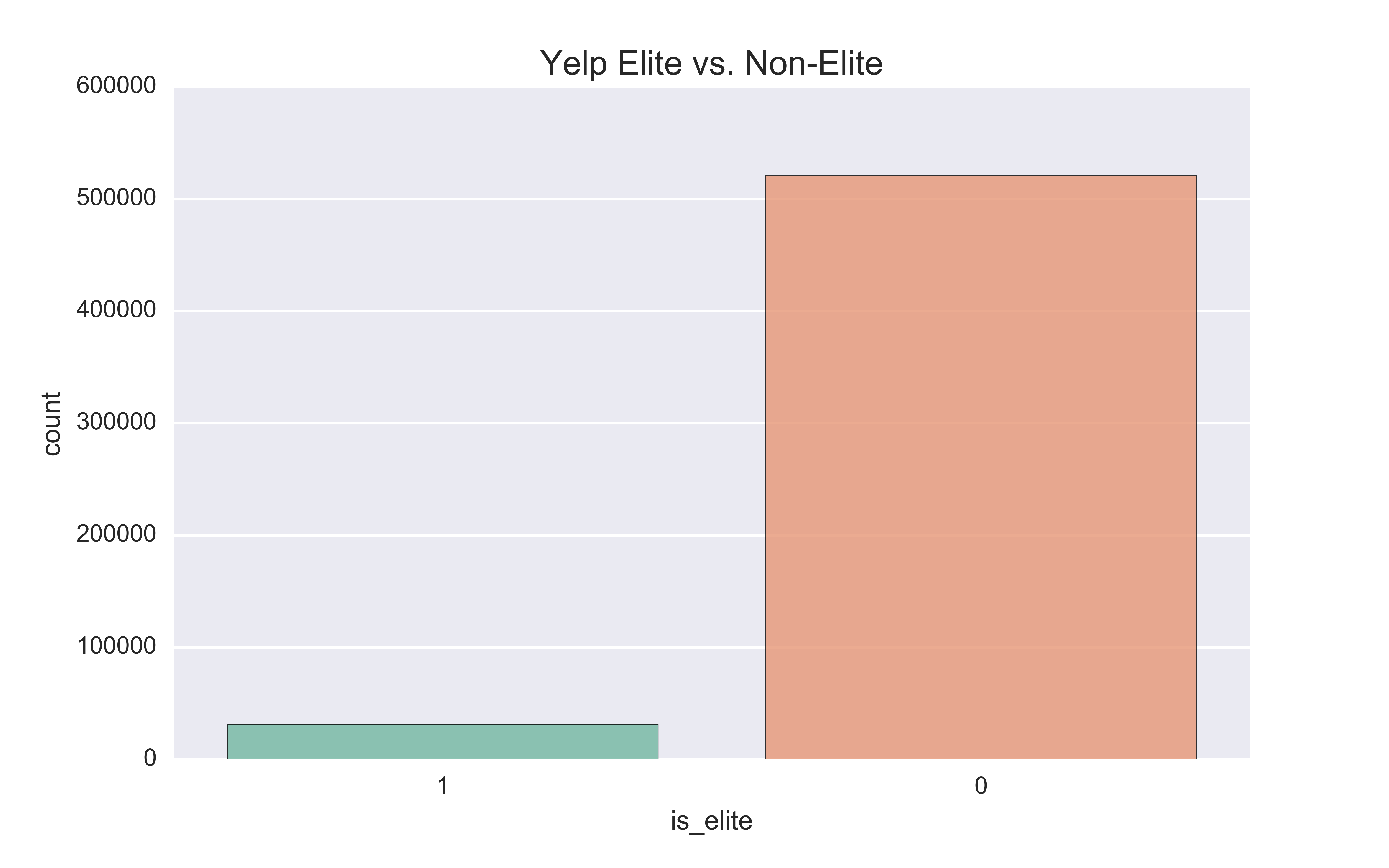

Unsurprisingly, Yelp elites make up only a tiny fraction of the overall population of users–only 6% (31,000 of the 520,000 total users in the dataset) are elite.

Looking at the scatter matrix below (elite users in blue and non-elite in green; apologies for overlapping x labels), we can see that:

-

The data is very skewed, with the majority of Yelp users not being power users, i.e. having a small number of reviews, fans, friends, votes, and compliments; and

-

As one would expect, the elite users exhibit and have more activity than the non-elite users. Another interesting related observation is that there are almost no non-elite users with high levels of activity; Yelp has either given elite status to all users once they’ve hit a certain activity threshold, or users that haven’t been awarded elite status after a certain activity threshold have stopped being active on the site.

Since non-elites account for 94% of my data set, there’s a clear class imbalance problem. I built a simple logistic regression and random forest classifier model using the easily accessible features (review count, number of friends, number of fans, number of compliments, number of votes, years on Yelp, and average review stars; all normalized, except for average stars and years on Yelp) to see how the models would fare beyond a baseline model of just predicting non-elite every time. The numbers below represent the mean scores for a five-fold cross-validation model:

| Baseline | Logistic Regression | Random Forest Classifier | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 94% | 97.5% | 97.5% |

| Precision | N/A (0%) | 81.6% | 82.0% |

| Recall | N/A (0%) | 73.0% | 70.9% |

The model performed surprisingly well for such an imbalanced data set. Below are the logit coefficients and their impact on the (log) odds of being elite:

| Feature | Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Review count | + 1.3 |

| Compliments count | + 0.7 |

| Average stars | + 0.4 |

| Votes count | + 0.2 |

| Friends count | + 0.1 |

| Fans count | + 0.1 |

| Years on Yelp | - 0.2 |

Again, unsurprisingly, more activity is positively correlated with higher odds of being a Yelp elite. The two things that I found relatively unexpected from this initial run of the model were that 1) more positive reviews (higher average stars) makes you more likely to be a Yelp elite, and 2) being on Yelp longer actually decreases your odds of being elite.

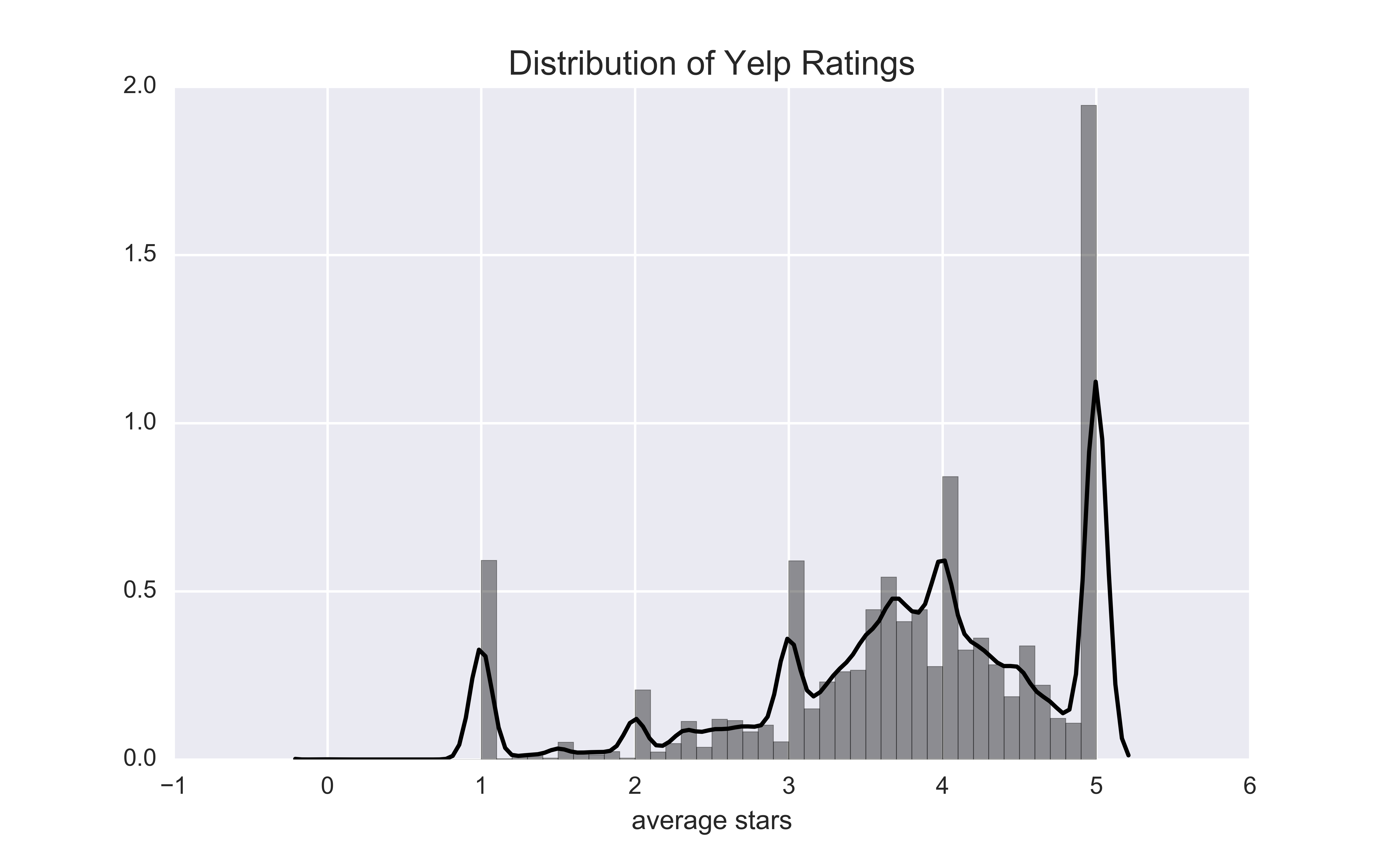

A slight tangent, but–I also wanted to share this distribution plot of average stars across all users; as you can see, the majority of ratings on Yelp are actually exceedingly positive, with five stars being the highest average rating, followed by four stars. I found this interesting since I expected there to be more one star ratings, since my inclination to write reviews is always when I have a negative experience at a business (but maybe I’m just crabby).

Not too shabby for a week’s worth of work (among a few other things)! For next steps, I’m hoping to dig into finding patterns in review styles for elites by doing some natural language processing and sentiment analysis. I’ll also try to upsample my data set to try and address the class imbalance issue and hopefully fine tune my model.

Stay tuned! And feel free to shoot me an email if you have any thoughts/comments on my work so far.